State Oversight Matters

The State Oversight Academy’s blog, State Oversight Matters, tackles the importance of state legislative oversight; practical matters in conducting investigations, holding effective public hearings, and working together to find the facts; specific topics requiring oversight such as appropriations, corrections, foster care; SOA activities and updates; and other topics of interest!

Checks and Balances Under Fire This Independence Day

This Fourth of July, while celebrating American independence, we must also confront threats to our democratic system and recommit to protecting checks and balances in government.

How States Can Prepare for Federal Fiscal Uncertainty

As federal funding grows uncertain, states must shift from reaction to preparation. Proactive oversight, data-driven planning, and public engagement can help legislators protect vital services and build fiscal resilience before federal cuts force change.

Beyond the Buzz: How State “DOGE” Committees Can Drive True Reform

As states rush to create DOGE-inspired committees to “streamline” government, are they cutting waste—or just cutting corners? Before wielding the axe, lawmakers must decide: will facts drive reform, or is “efficiency” just another political buzzword?

Bear-eaucracy Killed the Grizzly

A quirky Google alert sent us on a deep dive into Idaho’s legislative past, uncovering the story of a unique grizzly bear oversight committee and the surprising involvement of one of our advisory board members.

A Legislative Lifeline

Texas lawmakers halted an execution this month with a legislative subpoena to examine the implementation of the state’s ‘junk science’ law.

Congressional vs. Legislative Oversight: Notes from D.C.

The Levin Center’s recent Oversight Boot Camp in D.C. provided valuable insights into how congressional staff conduct fact-based, bipartisan investigations. While the resources available to Congress are more extensive, state legislatures can still achieve meaningful oversight by adopting a few key strategies.

Taking the Show on the Road: Conference Season 2024

In July, the State Oversight Academy team traveled over 7,000 miles across the U.S. to discuss legislative oversight at the Council of State Governments’ regional conferences.

Don’t Forget the Down-Ballot

State and local elections are often affected by “voter roll-off,” when citizens vote for candidates at the top of the ballot but not the bottom. Voting in down-ballot elections is critical – check out these tips on how to research your ballot!

Understanding the Importance of Cybersecurity for Critical Infrastructure: Why It Matters and How We Can Protect Ourselves

Cyber attacks targeting critical infrastructure are becoming increasingly severe. Here’s a look at how state governments are responding.

Oversight of Evolving Threats to Drinking Water

Auditors in Utah, Washington, and New York State are responding to growing threats facing our drinking water. By identifying risks, evaluating efficiency regulations, and assessing cybersecurity vulnerabilities, they offer important recommendations for improvement.

Building a Masterclass for State Legislators and Staff

The State Oversight Academy offers a new masterclass on Introduction to State Legislative Oversight — here’s how we put together the most crucial nuts and bolts for you!

We Make House (and Senate) Calls

What kind of State Oversight Academy would be best for your legislature’s needs? Learn about the types of trainings we offer to find out!

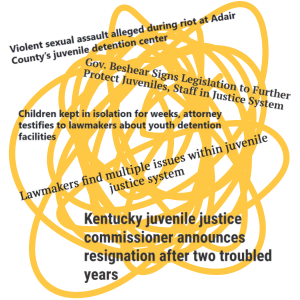

Juvenile Justice: An Investigation in Four Parts

Confronted with major issues in the state’s juvenile detention centers, the Kentucky legislature embarked on an in-depth investigation into the causes and possible solutions.

Eyes, Voice, and Teeth: Subpoenas in State Legislatures

Subpoenas are a powerful tool for legislative oversight. How can you use this authority to find facts and enhance your oversight investigations?

SOA Symposium in Review

The first State Oversight Academy Symposium featured three academic paper presentations, reviewed by practitioners. Learn more about the research and feedback on the event!

Look Diligently into Every Affair: Ombuds in State Government

Ombuds are important oversight partners. We look at legislative ombuds in three states to see how they use their authority to address public complaints about state government.

Reframing Casework as Oversight: Theory and Practice

Constituent casework is, in essence, the most direct form of oversight – it is the practice of asking people if the government is fulfilling its promises.

Interim Oversight

Many states utilize their interim session to perform important oversight work, either using interim committees, continuing standing committees, reviewing reports, or establishing studying committees.

State Legislature Oversight Wiki 2.0 is here!

The State Legislature Oversight Wiki just got too big – so we’ve introduced a new, searchable, version, full of new features and information!

Prison Operations Oversight: How Two States Find Facts on What Happens Inside Prison Walls

Colorado and Kansas address corrections oversight in very different and interesting ways. We explore these approaches and the effectiveness of each.

New Series Oversight Overview: Medicaid Oversight Committees

The State Oversight Academy is introducing new content called Oversight Overview, a video series that explores how state legislatures across the nation are performing oversight on a specific issue.

Deciding What to Investigate

With all the problems facing our nation, it can be hard to know what to prioritize. Here are some tips to help decide where you should focus your oversight efforts.

Five Reasons You Should do Oversight

State legislators have so much to do, and so little time. It’s easy to push oversight responsibilities aside so you can focus on other things – this is why you shouldn’t.